A FEW OTHER EVENTS FOR

MAY 8:

- It’s the birth date of Milton Meltzer (1915-2009), Tough Times, Mary Q. Steele (1922-1992), who sometimes used the pen name Wilson Gage, Journey Outside.

- It’s World Red Cross Day. Henry Dunant (1828-1910), born on this day, inspired the creation of the International Red Cross, as well as the Geneva Convention. He received the first-ever Noble Peace Prize in honor of his efforts.

- Best birthday wishes to the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show, first held on this day in 1877. Read Flawed Dogs: The Shocking Raid on Westminster by Berkley Breathed.

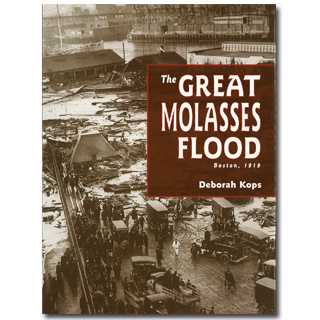

In the spring of 2012 several first-rate natural disaster books appeared, probably because of the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic. Besides the Titanic books, Sally M. Walker wrote a thrilling account of the Halifax Explosion of 1917 in Blizzard of Glass. Our book of the day by Deborah Kops, The Great Molasses Flood, takes a look at one of my favorite disasters, which took place in Boston in 1919.

Kops begins her account with exactly the right description: “Of all the disasters that have occurred in the United States, the Great Molasses Flood in Boston was one of the most bizarre.” How right she is. Imagine going out in the yard, or walking to school, hearing a loud explosion, and then finding yourself confronted with a wave of brown molasses— “that dark-brown sweet-and-sour liquid that sticks to everything.”

Kops sets the stage historically—the Spanish flu, Babe Ruth helps the Boston Red Sox win the World Series, and Prohibition on the horizon—and then she skillfully brings readers to lunch hour on January 15, 1919, when the huge molasses tank in Boston’s North End exploded. A wave of 2,300,000 gallons of molasses crested fifty feet high and swept away everything in its path including about a hundred men, women, and children at a speed close to 35 miles per hour. As the sticky substance made its way through the city it uprooted buildings, train lines, and the lives and property of Boston citizens.

Kops has effectively used original photographs from the event to show the story of Boston’s destruction; she scanned newspaper accounts and archival records of the trials that followed the disaster. Through these primary sources she brings readers right into the action, describing what it felt like and how it appeared to the citizens of the city. She does for the Molasses Flood what Walter Lord did for the Titanic in A Night to Remember.

For classroom or book group discussion purposes, the most important part of the book comes in the final chapters. Here Kops deals with the issues of industrial mismanagement. What do industries owe citizens for damage to life and property?

While reading this beautifully designed book, at one point I had to look out my window to make sure that no wave of dark brown could be seen. I am happy to report that Boston appears to be molasses-free this morning. But I am really grateful for narrative nonfiction like The Great Molasses Flood, which so vividly re-creates the events of another era.

Here’s a passage from The Great Molasses Flood:

Martin Clougherty, the owner of the Pen and Pencil, was in his bed rubbing the sleep from his eyes. His sister, Teresa, had just awakened him and was still in his bedroom. Suddenly, she let out a scream. “Something terrible has happened to the molasses tank!” she cried. Martin shoved the curtains aside and saw a murky liquid swirling outside. He gave his sister a hug and said, “Stay here.” Before he could investigate the situation, he heard his mother shriek in the kitchen. A momenet later Martin went sailing through the air.

A wave of molasses had lifted the Cloughertys’ house right off its foundation and pushed it across Commercial Street toward the elevated train. The house smashed against the columns supporting the tracks. The next thing Martin Clougherty knew, he was in a dark sea surrounded by pieces of his house, and he could not stand up. He was facing the ocean. Had he fallen in? he wondered. Clougherty managed to get his nose out of the goo and took some deep breaths. Something was floating on the surface, something he could use for a raft. He tried to swim toward it, but the dark sea was too thick, and he couldn’t move. Luckily a wave pushed the raft right in his direction. It was a bed, and Clougherty, who was still in his pajamas, climbed on top.

He looked around. His neighborhood had suddenly become a strange world. Sticking up out of the heavy liquid was a limp hand. Could it be his sister? As he pulled the body up onto the raft, he saw that it really was Teresa. And thank goodness, she was alive.

Originally posted May 8, 2012. Updated for .

And a good chapter book to read on the subject is “Joshua’s Song” by Joan Hiatt Harlow.

I’m used to tornados by the dozen, but being suffocated by a 50 foot wave of molasses was never something I would have envisioned until now.

As I started reading this, I thought it was fiction. A city drowning in syrup? Oh come on. I thought Willie Wonka was going to come on stage any moment.

What an amazing bit of history.

Yes, it does sound like fiction — but even until the 1970s those living in the North End of Boston claimed they could still smell molasses!

Latest news: Maurice Sendak died today. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/09/books/maurice-sendak-childrens-author-dies-at-83.html?emc=na

I’ve always loved the story of the molasses flood. A great aunt told me about it when I was a kid and even claimed to have been working nearby at the time. Born in 1899 she might have been telling the truth! The pictures in Kops’ book are so much better than the same photos used in Puleo’s adult book about the fllood, Dark Tide. I think it is because they are so much bigger you can see all the details, the molasses dripping off a ladder for example.