A FEW OTHER EVENTS FOR

NOVEMBER 30:

- It’s the birth date of Lucy Maud Montgomery (1874–1942), Anne of Green Gables, Jonathon Swift (1667–1745), Gulliver's Travels, Samuel Clemens (1835–1910), pen name Mark Twain, Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer.

- It’s also the birth date of British statesman Winston Churchill (1874–1965). Read Winston of Churchill by Jean Davies Okimoto.

- The steam locomotive Flying Scotsman becomes the first to officially exceed 100 mph in 1934. Read Steam, Smoke and Steel by Patrick O’Brien and Superpower: The Making of a Steam Locomotive by David Weitzman.

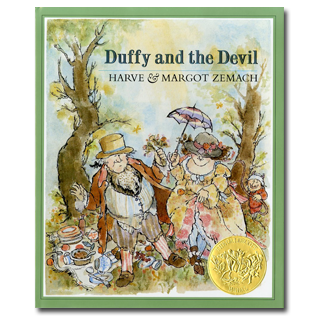

We’ll end the month of November with another birthday celebration, this time of one of the finest book illustrators of the twentieth century, Margot Zemach, born in 1931. Strangely, and I have never figured out why, male illustrators for children outnumber and generally outrank, in terms of accolades, their female counterparts. But Margot Zemach could hold her own with the men of the field, winning the Caldecott Medal for Duffy and the Devil.

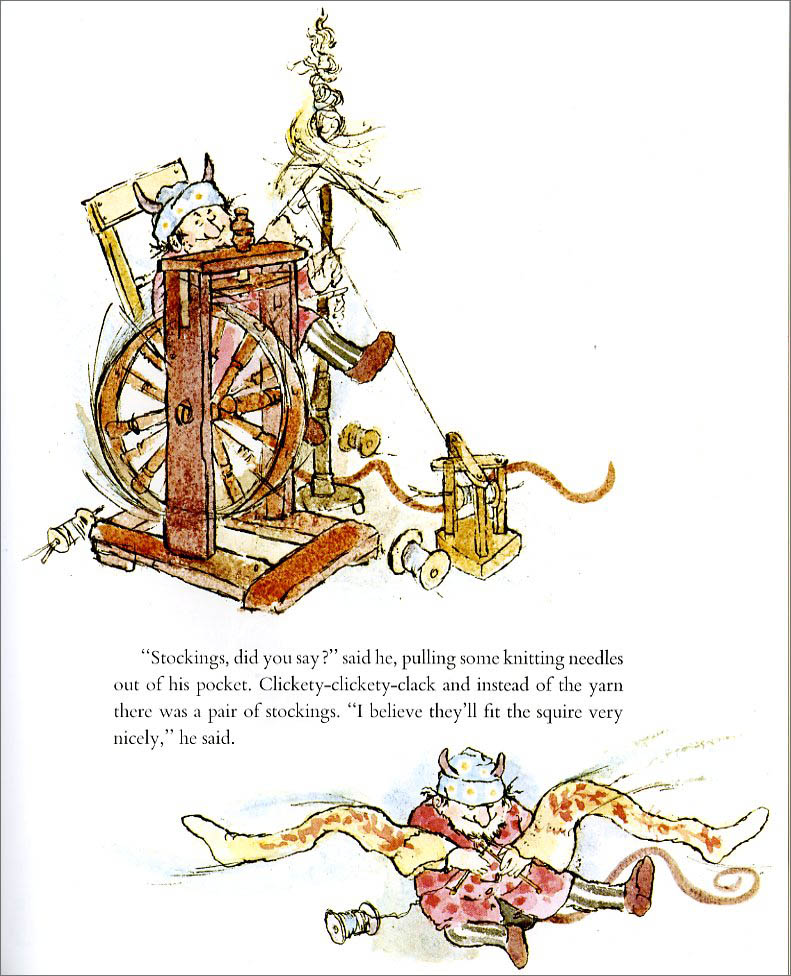

Zemach came to her career in children’s books after studying at the Los Angeles County Art Institute and the Academy of Fine arts in Vienna, Austria, on a Fulbright Scholarship. Collaborating with her husband, Harve, on her first book, A Small Boy Is Listening, she depended on his writing talents for many of her publications. Often he provided delicious language for stories; she gave them life in her animated artwork. Not only could she draw like an angel—all of the work is based on strong composition and line—but she had an impeccable sense of design. To look at her work feels like going on a walk in a well-laid-out rose garden. She knew how to combine art, text, and type to make reading a pleasure. And white space—where the white paper is allowed to show through. She had no fear of white space!

The Zemachs often used folktales for the basis of their books. One of their best, It Could Always Be Worse, a Caldecott Honor, stems from a Yiddish folktale. Her Caldecott winner, Duffy and the Devil, was based on a Cornish folktale similar to Rumpelstiltskin. But nothing in her artwork seems borrowed or copied. Every book had freshness to the approach and liveliness in the illustration. I have always thought of Margot Zemach as a modern-day Randolph Caldecott, the great 19th century English illustrator. Her characters dance and move across the page—and she always manages to bring out the humor of the text and situation.

Children’s literature allows readers to bring all of their experiences to a book each time they pick it up. I was a young Horn Book reviewer when I first encountered Zemach’s work and fell in love with Duffy and the Devil. To humor me, Paul Heins, editor of The Horn Book and a great Zemach fan, of both Harve and Margot, allowed me the privilege of reviewing it for the magazine—because I was so passionate about the book. When this beautiful and spirited book won the Caldecott Medal, I felt as if I had won that medal myself! Every time I pick up the book, I read not only this story, but part of my story as well. That is what great children’s books do.

In 1989 Margot Zemach died of Lou Gehrig’s disease. But as with all our great creators, her books remain. So today I hope you pick some of them up and join me in celebrating what would have been her 80th birthday.

Here’s a page from Duffy and the Devil:

Originally posted November 30, 2010. Updated for .

What a wonderful story Anita.

I have just read something extraordinary here, Something I have never seen before. An exact description of what happens to me every time I read, or reread a children’s book. In addition, I have discovered an unread treasure.

What a delightful website. Every morning this is he first place I go on the net. (It used to be the BBC news site. Now, they’re second.

Excuse me while I go find Duffy and the Devil. I’ve never read this one before and I can’t wait to find it.

Kind regards

G. Perry

Thanks for your comments. I am honored to come before the BBC! Anita

I love the enriching backstory you provide for each selection, Anita. I’m thrilled to find the Children’s Book Almanac – thanks to Leda’s interview with you! Now I will catch up in the Archive and stay with you.

Best wishes,

Joyce Ray

I enjoyed this story but I feel it is going to be difficult for me to use in my classroom. Some of the phrases will need to be explained and it will take a lot of time to go through and explain each part to the class. I like using this website to find new books I can have not read yet but want to read and then share with my third graders. Thank you.

Over 30 years ago, in a review in New York Magazine, Karla Kuskin said that Margo Zemach drew like “an intoxicated angel.” I’ve always loved this description.

I think Brock Cole has a good bit of that intoxication in his picture book work, don’t you?

Leda: An interesting way to describe them both — certainly both from the same tradition.

Oh, Cindy, don’t you think it’s worth the time? That’s what a good teacher does, and you sound like a great teacher.

Which phrases would be hard to explain? Just looking at this one page, I can imagine that even knitting needles would be hard to explain to contemporary third graders–the very idea that people used to knit stockings! But there’s such richness in this diversity of books Anita so deftly introduces on the Almanac. I wouldn’t want to choose only the easy-to-understand ones. (I do understand that the minutes you have with your students are precious.)

Thanks, Anita, and everyone, for this good conversation.

Helen: I agree — and thank you for this impassioned plea for rich vocabulary in picture books. I am always reminded of Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit; she used soporific in relationship to lettuce. A few people have had to explain that word over the years!

Hi Anita,

Your feature brought out fond memories of working with Margot on two of her books towards the later part of her career, The Chinese Mirror and The Enchanted Umbrella.

Her lively calligraphic line work appears effortless; yet I know how conscientious she was about her character depiction. Every detail: the line weight, size of image in proportion to the page, the pacing, et al., all counted. Not a single wasted stroke! I’ll never forget the stacks and stacks of character studies. It was fascinating to see how they evolved progressively. And her earthy humor. I miss her.

Thank you for sharing her birthday anniversary with us! Oh, and if you have any friends who are considering entering the law profession, gift them with a copy of The Judge.”

“When this beautiful and spirited book won the Caldecott Medal, I felt as if I had won that medal myself! Every time I pick up the book, I read not only this story, but part of my story as well. That is what great children’s books do.” –

Beautiful! Simply beautiful! Thanks for sharing your stories and favorite books with us. Reading the CBADA is always the highlight of my day.

Joy: Thanks for your wonderful comments about working with Margot.

John: Your support for the Almanac has kept me going!

Cindy, 3rd graders will love A Penny a Look and The Judge, and neither should require much explanation, just a wry sense of humor. Both are wonderful to read aloud.

Madeleine L’Engle, in her book A Circle of Quiet, discussed authors’ use of words that children might not recognize:

“I have a profound conviction that it is most dangerous to tamper with the word. I’ve been asked why it’s wrong to provide the author of a pleasure book, a non-textbook, with a controlled-vocabulary list. First of all, to give an author a list of words and tell him to write a book for children using no word that is not on the list strikes me as blasphemy. What would have happened to Beatrix Potter if she had written in the time of controlled vocabulary? Lettuce has a soporific effect on Peter Rabbit. “Come come, Beatrix, that word is beyond a child’s vocabulary.” “But it’s the right word, it’s the only possible word.” “Nonsense. You can’t use soporific because it’s outside the child’s reading capacity. You can say that lettuce made Peter feel sleepy.”

I shudder.

To give a writer a controlled-vocabulary list is manipulating both writer and reader. It keeps the child within his present capacity, on the bland assumption that growth is even and orderly and rational, instead of something that happens in great unexpected leaps and bounds. It ties the author down and takes away his creative freedom, and completely ignores the fact that the good writer will always limit himself. The simplest word is almost always the right word. I am convinced that Beatrix Potter used “soporific” because it was, it really and truly was, the only right word for lettuce at that moment.”